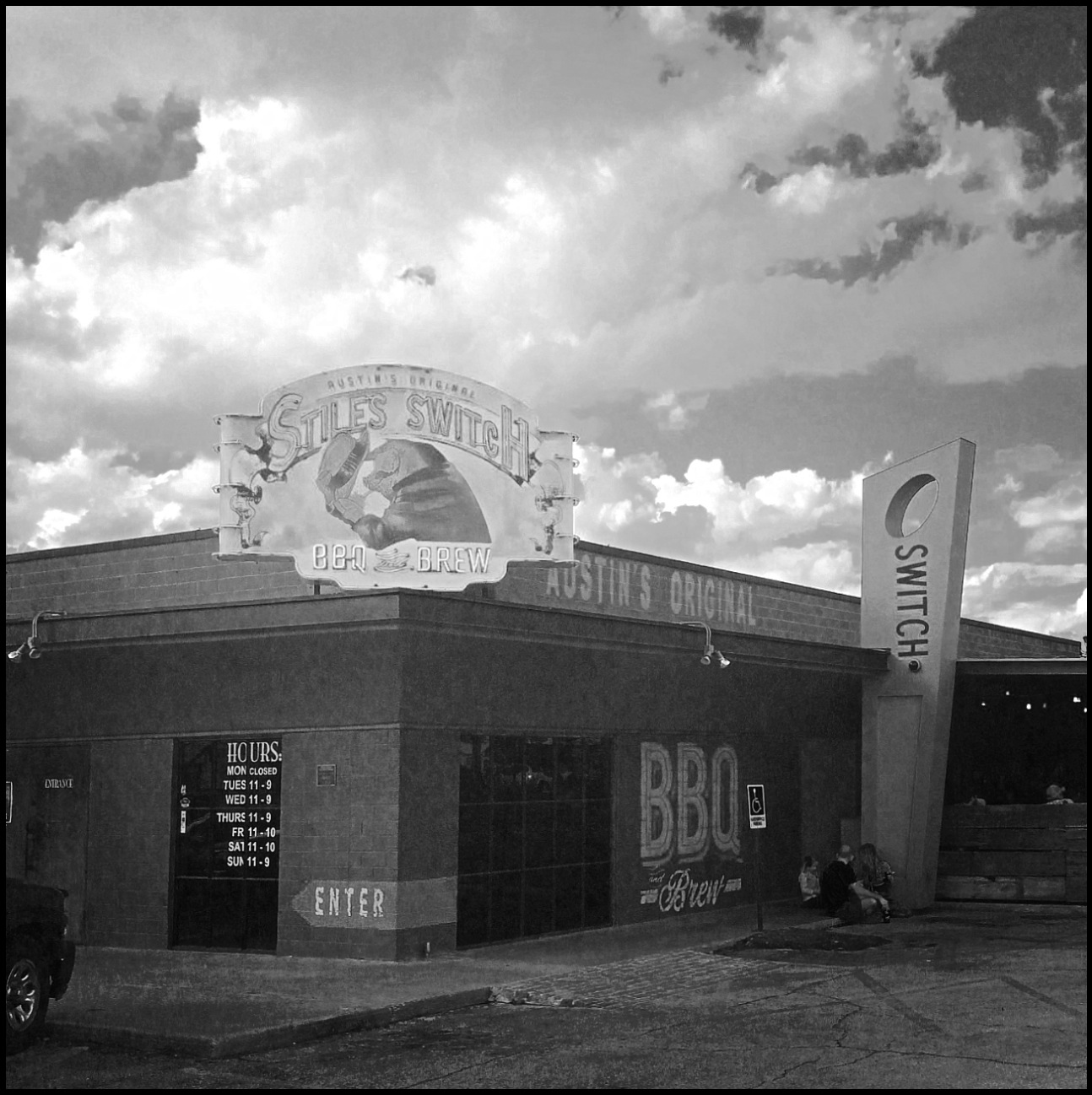

Aaron Franklin, proprietor of the Franklin Barbecue in Austin, Texas, has been lauded for his pit master skills, specifically in smoking beef brisket. Bon Appetit anointed his fare the best barbecue in America, and he was awarded Best Chef: Southwest by the James Beard Foundation. Barbecue lovers line up hours in advance of the restaurant’s 11 AM opening, and the limited supply of brisket, ribs, chicken, pulled pork, and sausage usually sells out by 2 PM.

Franklin’s prized brisket is priced at $20 a pound, in line with local rivals County Line ($20.58), Ruby’s ($21.95), and Rudy’s ($17.58). Given the high demand for his cuisine, it’s fair to wonder, “Why doesn’t Mr. Franklin raise prices?”

Economists are typically incredulous about sellouts — events such as rock concerts and sporting events, as well as in-demand products like Mr. Franklin’s barbecue. Their standard advice: “Raise prices — set the market clearing price where demand equals supply.” But in most cases, I believe this armchair advice can be detrimental to a business. Why? Because customers have long memories.

What economists often fail to understand is price creates an emotional response within customers that affects their loyalty. Getting a good deal generates euphoria, while high prices provoke feelings of anger over getting ripped off. As an extreme example of that, a pharma company recently raised prices by 5,000% and was met with national outrage. Conversely, it’s common to experience elation over finding a bargain – consider the excitement as stores open their doors on Black Friday.

Emotions generated by a price formulate a perception of a business – “low,” “reasonable,” or “high” – which affects future purchase decisions. Before we as consumers make a purchase, we search to find the best price. Often times, it’s easy to rely on memories of past pricing experiences with a business. We revisit stores we recall as offering “fair” prices and avoid ones where we felt the sting of being taken advantage of. Due to consumers’ long memories, the price a business sets today directly affects future purchase decisions.

When business is strong, it’s often best to resist the urge to boost prices. Think of tempering price increases as a form of “insurance” against a future drop in demand. In Mr. Franklin’s case, Bon Appetit may decide another restaurant serves the best barbecue in America (or even in Austin). It’s also possible that cheaper competitors may pop up close by that are “good enough,” or overall demand may drop (due to recent health scares from processed meat, for instance). If high prices were set during a moment of good times, it will be challenging to communicate lower prices to customers. Banners declaring “new low prices” can damage a brand, by coming off as desperate. Alternatively, a low price embedded in consumers’ minds will help keep the lights on during slow periods.

There are steps that businesses can take to squelch the emotions brought on by high prices. Restaurants, for instance, offer premium-priced set menus on popular holidays such as New Year’s Eve and Valentine’s Day. Since the product is different (set vs. a la carte menus), this minimizes diners associating the higher price with the restaurant’s everyday fare. For a service business, keeping price-related emotions intact can be as simple as explaining, “We are super-busy right now – as a result, we’ve had to raise prices temporarily to cover overtime. You can buy right now or I can contact you when we are less swamped and our prices are lower.”

A handful of industries have heavily invested to educate customers that prices will vary over time. We’ve come to expect fluctuating prices from airlines and hotels. The goal of educating customers is so they understand and accept prices will be high at times, but that they also realize there are “off-peak” options available at a discount. As a result, most of us aren’t offended that prices at fancy resorts are astronomical during Christmas-to-New Year’s week compared to other time periods. Training customers to expect varying prices can be a significant undertaking though. Despite its best efforts, for instance, Uber has faced strong backlash over its surge pricing strategy, which can often be seven times the normal price.

There are two key issues to consider before boosting prices during a period of strong demand. First, how confident are you that the good times will last? Second, what initiatives should be taken today so if need be, price can be gracefully rolled back? For many businesses, it may make sense to forego a few extra dollars of momentary profit and instead follow what Aaron Franklin practices in both setting prices as well as smoking meat…go low and slow.